Thoracic Deformities

Thoracic deformities are various forms and depths of curvature of the sternum and the anterior parts of the ribs, leading to a reduced volume of the chest cavity, compression and displacement of the mediastinal organs, causing functional impairments of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems, and manifesting with varying degrees of cosmetic defects.

Congenital thoracic deformities, primarily congenital pectus excavatum (funnel chest) and pectus carinatum (pigeon chest), are common developmental defects of the sternum, ribs, and diaphragm.

Pectus Excavatum (funnel chest, infundibuliform) was first described by Bauhinus in 1600 and more thoroughly by Eggel in 1870. The causes are not fully understood, but many authors emphasize its distinctly congenital nature; it is associated with dysplastic changes in the cartilaginous and connective tissues of the chest and often has a familial (genetic) predisposition and a tendency to progress.

Clinically, there are three stages of the disease:

- Compensated

- Subcompensated

- Decompensated

At the compensated stage, patients only have a cosmetic defect with no complaints or functional disturbances.

At the subcompensated stage, significant functional impairments of the lungs and cardiovascular system often appear.

The clinical picture of pectus excavatum depends on the child’s age:

- Infants: Deformity often appears in the first months after birth as a slight depression. A characteristic sign is the “paradoxical inspiration” symptom (sternum and ribs retract during inhalation). It may also present with paradoxical or, less commonly, stridorous breathing due to compression and displacement of the trachea by the heart, or dysphagic symptoms (regurgitation and vomiting after feeding). The deformity is most noticeable when the child cries. It is difficult to predict progression in infants. According to data, in nearly half of cases, the depression deepens as the child grows. The rib edges begin to protrude, forming a transverse groove above them (pseudo-Harrison’s groove), sometimes mistaken for signs of rickets.

- Preschool children: Gradual progression to a fixed curvature of the sternum and ribs occurs, posture changes, and thoracic kyphosis worsens. Shoulders appear dropped, and rib edges are raised. The deformity usually does not cause serious cosmetic concern but lung and heart changes become more noticeable, with frequent colds. The child may lag in weight and physical development, abdomen protrudes, and postural issues like scoliosis and kyphosis develop, along with vision problems, dental caries, flat feet, pallor, and gastrointestinal issues like bile duct dyskinesia and stool irregularities.

- School-age children (7-9 years, first active growth phase): Deformity worsens progressively; posture disorders increase. Children often appear undernourished with pale skin, fatigue easily, experience shortness of breath, palpitations, chest pain, irritability, poor appetite, frequent respiratory infections, tonsillitis, bronchitis, pneumonia. The deformity becomes fixed, chest excursion decreases, and lung capacity reduces by 18-30%. Changes in external respiration parameters and cardiovascular function are noted. Pressure of the sternum on the heart causes displacement, rotation, and arrhythmias. Besides somatic complaints, children develop inferiority complexes due to the deformity becoming noticeable to peers.

Clinical and Diagnostic Features of Pectus Carinatum (Pigeon Chest):

Unlike pectus excavatum, this deformity arises at an older age. The protruding sternum with depressed rib edges gives the chest a characteristic pigeon-like shape. It increases with growth, mainly causing cosmetic concerns, but functional issues such as shortness of breath, chest pain, and fatigue may also occur.

Diagnosis:

Diagnosis of pectus excavatum and pectus carinatum is straightforward based on clinical presentation and additional studies.

An essential examination is the analysis of external respiratory function in children with thoracic deformities. Spirometry has shown a decrease in key lung volume indicators in 95% of operated patients, especially vital lung capacity, respiratory rate, and tidal volume by 18% to over 30%. Scintigraphy reveals significant microcirculation changes in the lungs. ECG often shows heart axis deviations and sinus arrhythmia, more frequent in older children. Radiography, CT, and MRI are critical in assessing the deformity’s type and severity, anomalies of the sternum, ribs, spine, and organ displacements in the chest cavity (heart, lungs, etc.).

Treatment:

Currently, conservative treatment methods for congenital pectus excavatum and pectus carinatum are largely rejected by most orthopedists and surgeons.

Surgery is considered the only method for complete correction of chest deformities and prevention/treatment of secondary pathological changes in thoracic organs, especially the cardio-respiratory system.

Indications for Surgery:

- Absolute indications include functional impairments of the lungs and heart (subcompensated and decompensated stages), commonly seen in children aged 3-5 years with deformities of grades II-III.

- Orthopedic indications require correction of posture and spinal curvature.

- Cosmetic reasons, due to physical defects causing psychological distress, which increase with age.

Surgery is preferably performed between ages 3 and 10 when the chest is still developing, and secondary spinal deformities are mild.

Preoperative preparation is similar to that for any major thoracic surgery.

Surgery

Currently, the most widely used operations involve internal metal fixators. The “gold standard” is rightfully considered the Nuss procedure (developed by American surgeon Donald Nuss).

The surgery is performed under general anesthesia. The patient is positioned with both arms abducted to allow access to the lateral chest wall. A transverse incision about 2.5 cm long is made on each lateral chest wall between the anterior and posterior axillary lines. A curved clamp is passed through the mediastinum until it appears on the opposite side. Using a traction tape, a pre-shaped steel bar is pulled through. The bar, with its convex side facing backward, is passed under the sternum. Once in position, the bar is rotated 180 degrees so that the convexity faces forward, thereby lifting the sternum and anterior chest wall into the desired position. If necessary, a second bar is placed above or below the first. If the bar is unstable, a crossbar 2-4 mm in length is attached to one or both ends. When two bars are used, crossbars connect both ends to form a rectangular frame. The wounds are closed layer by layer.

Considering some shortcomings of the classic Nuss method, we use a modified minimally invasive thoracoplasty (proposed by Saint Petersburg Pediatric University). The main differences in surgical technique include a change in surgical access and extraplural placement of the bar under manual control without video assistance.

Diagram of the modified Nuss procedure:

- A – Surgical access scheme:

1 – transverse skin incision. - B – Site of corrective bar insertion:

2 – intercostal space,

3 – rib,

4 – sternum,

5 – bar insertion point. - C – Extrapleural passage of corrective bar:

3 – rib,

4 – sternum,

6 – pleura,

7 – corrective bar,

8 – retrosternal space. - D – Final correction of the deformity:

3 – rib,

4 – sternum,

6 – pleura,

7 – corrective bar,

8 – retrosternal space.

Longitudinal skin incisions 3-8 cm long are made symmetrically on both sides at the level of the 5th-6th ribs in the midclavicular line projection. The 5th-6th ribs are exposed layer by layer on both sides. Using blunt dissection and minimal physical effort with fingers, a tunnel is created behind the sternum (the original method used instruments for this). Unlike the original, we insert a guidewire into the tunnel from left to right under finger control. Lavsan ligatures are fixed to the end of the guidewire. The steel bar, shaped according to the optimal correction needed, is attached to the ligatures. The bar is then pulled through the tunnel from right to left under finger control with the curve facing backward. The bar is clamped with forceps on both ends and rotated 180 degrees to correct the deformity. Blunt dissection is used to create a submuscular tunnel for the bar on both sides. The bar is then fixed in place. The wounds are closed tightly layer by layer, with intradermal sutures on the skin.

Advantages of our modified Nuss surgical correction:

- During retrosternal space mobilization, the risk of pleural injury is minimized.

- Surgical access reduces trauma when passing the bar.

- Implant placement is done under manual control without video assistance.

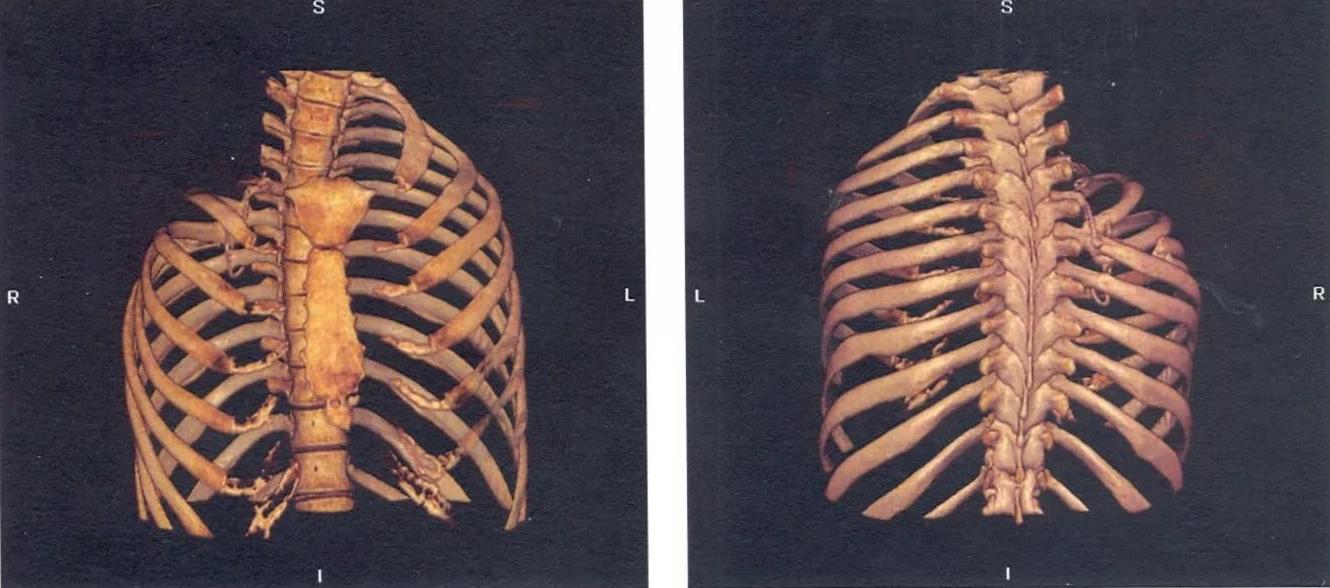

Clinical Case

Appearance and X-ray of a 10-year-old patient with grade III pectus excavatum before surgery.

Appearance and X-ray of the same 10-year-old patient after surgery — 100% correction of the deformity.

Summary:

Treatment of pectus excavatum is exclusively surgical; no conservative methods lead to correction of the anterior chest wall!

The optimal age for surgery is preschool (3-7 years), as the body can still compensate for pathological changes in internal organs and the child avoids psychological trauma related to appearance.modificările patologice ale organelor interne, iar copilul nu are traume psihologice datorită aspectului său.