Congenital scoliosis is a rare condition, occurring in only 1 in 10,000 infants, which contrasts with scoliosis that develops during childhood or adolescence.

ACongenital scoliosis arises due to abnormalities during the first 6 weeks of pregnancy and is considered a malformation that causes severe and typically rapidly progressing deformities. These deformities require orthopedic treatment throughout the growth period, significantly shortening life expectancy and decreasing quality of life, and are almost impossible to correct surgically.

This anomaly is often associated with severe developmental defects of internal organs, limbs, and the spinal cord, whose clinical manifestations become dominant and prevent timely correction of the spinal deformity. The majority of studies on vertebral segmentation disorders focus on age periods when the resulting spinal deformities are nearly incurable.

Main Types of Congenital Spinal Deformities

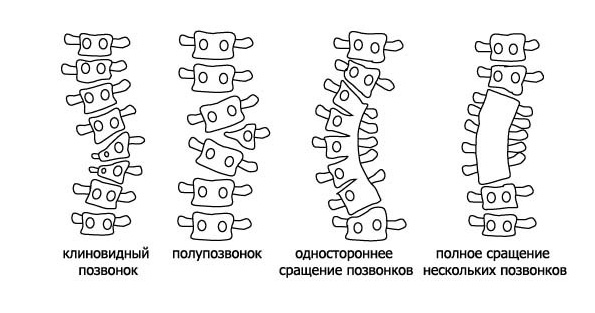

There are two main causes of congenital scoliosis: segmentation defects and formation defects.

In some cases, if visible scoliosis is present, compensatory curvature may develop. In this situation, the spine curves in the opposite direction from the scoliosis in order to maintain an upright posture. The vertebrae in the compensatory curved section of the spine are of normal appearance.

Segmentation defects occur when two or more vertebrae partially fuse together. At the sites of fusion, growth is slowed down, while on the opposite side, growth is more intense, leading to spinal deformity.

The most common form of congenital scoliosis is formation defect, which arises due to vertebrae forming in abnormal shapes.

Congenital Scoliosis: Types, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Incomplete Vertebral Formation

During the formation of the spine in the womb, some sections may fail to develop fully. This condition is called hemivertebra, and it often results in a wedge-like spinal angle. As the child grows, the angle increases. Hemivertebra can occur in multiple vertebrae. When multiple underdeveloped vertebrae are present, they begin to compensate for each other, helping to maintain spinal structure.

Vertebral Non-segmentation

As the embryo grows, the spine initially forms as a continuous column, which later divides into segments known as vertebrae. If this division fails properly, two or more vertebrae may fuse together. This partial fusion hinders proper spinal development, leading to curvature as the child grows.

Combination of Partial Vertebral Formation with Non-segmentation

This combination of two previously described types of congenital scoliosis is the most serious pathology, requiring immediate treatment. The child will need surgery in childhood to prevent further curvature.

Compensatory Curvature

In some cases, if visible scoliosis is present, compensatory curvature may develop. In this situation, the spine curves in the opposite direction from the scoliosis in order to maintain an upright posture. The vertebrae in the compensatory curved section of the spine are of normal appearance.

- Diagnosis of Congenital Scoliosis

- There are several signs that help determine the malignancy of congenital scoliosis. Abnormalities in the thoracic spine usually progress more rapidly than those in the lumbar spine. The presence of multiple abnormal vertebrae on one side is also an unfavorable sign. Since rapid growth is observed in children under 5 and during adolescence, these periods are critical for monitoring a child for scoliosis.

- Examination

- If congenital scoliosis is suspected, standard X-rays of the spine should be taken in both the lateral and anteroposterior projections. This is typically enough to identify abnormal vertebrae, their type, and the degree of deformity. If necessary, a CT scan can be performed. MRI is recommended to exclude anomalies related to the spinal cord. Congenital scoliosis is often associated with congenital abnormalities of internal organs. In 25% of cases, it is associated with urinary system anomalies, and in 10% with cardiovascular system anomalies.

- Treatment Methods

- Corset Therapy

- For progressing deformities in the range of 25–45°, a corset is prescribed. To determine the effectiveness of the corset, X-rays should be taken in the bent position, both to the right and left. If the deformity is rigid, the corset will be less effective. Flexible deformities respond better to corset therapy. The goal of the corset is not to correct the deformity but to stop its progression. A good outcome is considered when the deformity before and after treatment remains the same.

- Plaster Casting

- For significant rigid spinal deformities, plaster casts are used. The goal of casting is the same as that of a corset. The only difference is that these casts cannot be removed on their own, and physical exercises cannot be performed while wearing them. Plaster casts are changed every 8–14 months.

- Surgical Treatment

- If active treatment with a corset or cast does not yield the expected results and the deformity continues to progress, surgical intervention is indicated. One of the main objectives of surgery for congenital scoliosis is to allow for continued growth of the spine and thoracic cage.

- The spinal fusion technique on the side opposite to the block is now the accepted standard for stabilizing surgeries in cases of vertebral segmentation disorders.

- The primary goal of surgery is to reduce or eliminate the possibility of asymmetric growth of vertebrae, thus reducing or preventing further spinal deformity during growth. This goal is achieved through spinal fusion on the side opposite to the congenital block or a full 360° fusion.

- Surgical Approach in Congenital Scoliosis

- Stage I: Disc removal + corpectomy on six levels on the convex side (“balancing spinal fusion”).

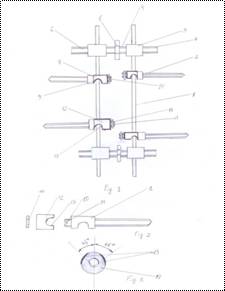

- Stage II: Deformity correction using a device developed and applied at our clinic, with blocking on the convex side and preserving the possibility of “growth” on the concave side (patent MD. 77). The device “grows” with the spine due to the ability of the rod to slide in the fixing elements (pedicle screws) (patent MD. 77).

Clinical Case.

Appearance of a patient 7 years after surgery.

2004 – До операции

2012 – После операции

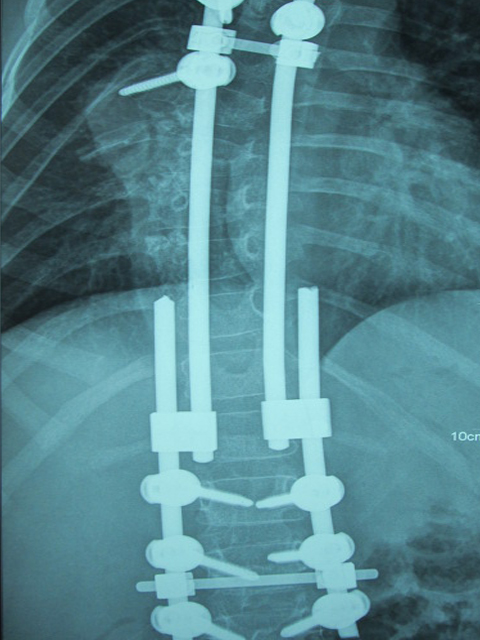

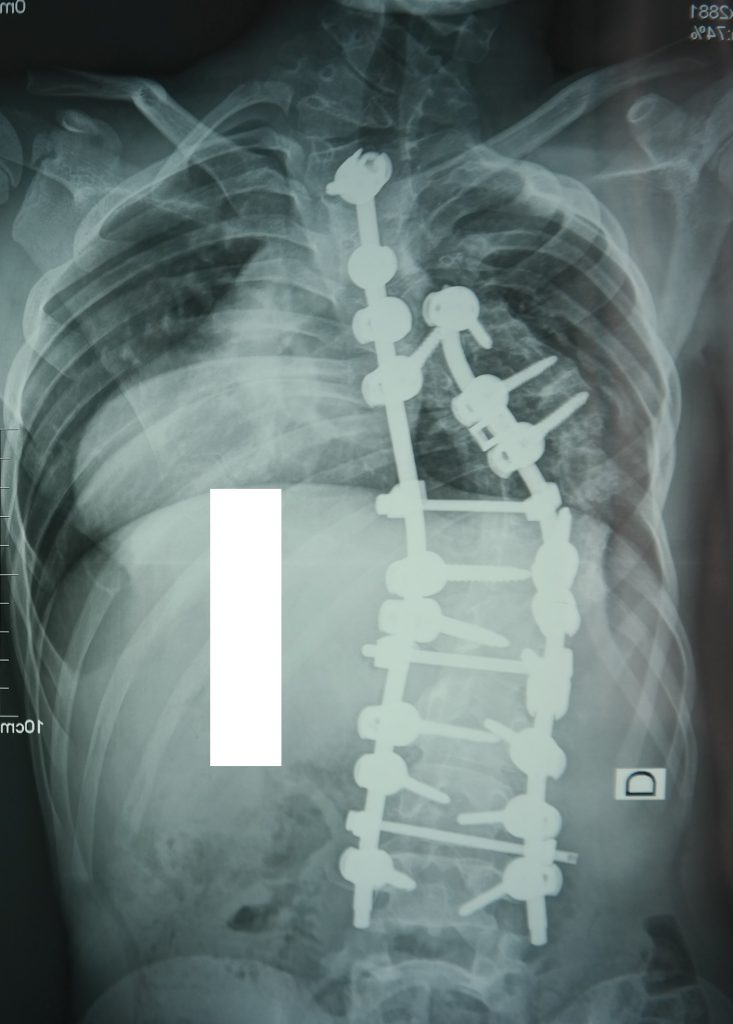

A 6-year-old patient with congenital scoliosis, Stage IV. Stage 2 of surgical treatment: Blocking “balancing” corpectomy on the convex side of the deformity. Correction and fixation with a growing transpedicular connector system.

Before Surgery

2 Years After Surgery

Congenital Scoliosis, Final Correction at 13 Years Old, 5 Years After Surgery

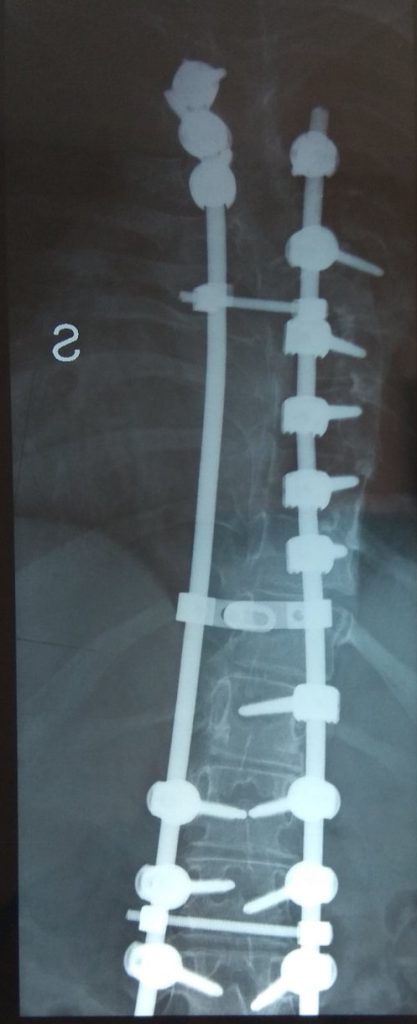

Clinical Case. The patient was admitted at the age of 8 with congenital scoliosis, Stage IV. Discectomy was performed on the convex side followed by staged correction.

Before the surgery

Age: 8 years

7 years after surgery.

Age: 15 years